Arrival of the Declarations of Independence to Honduras

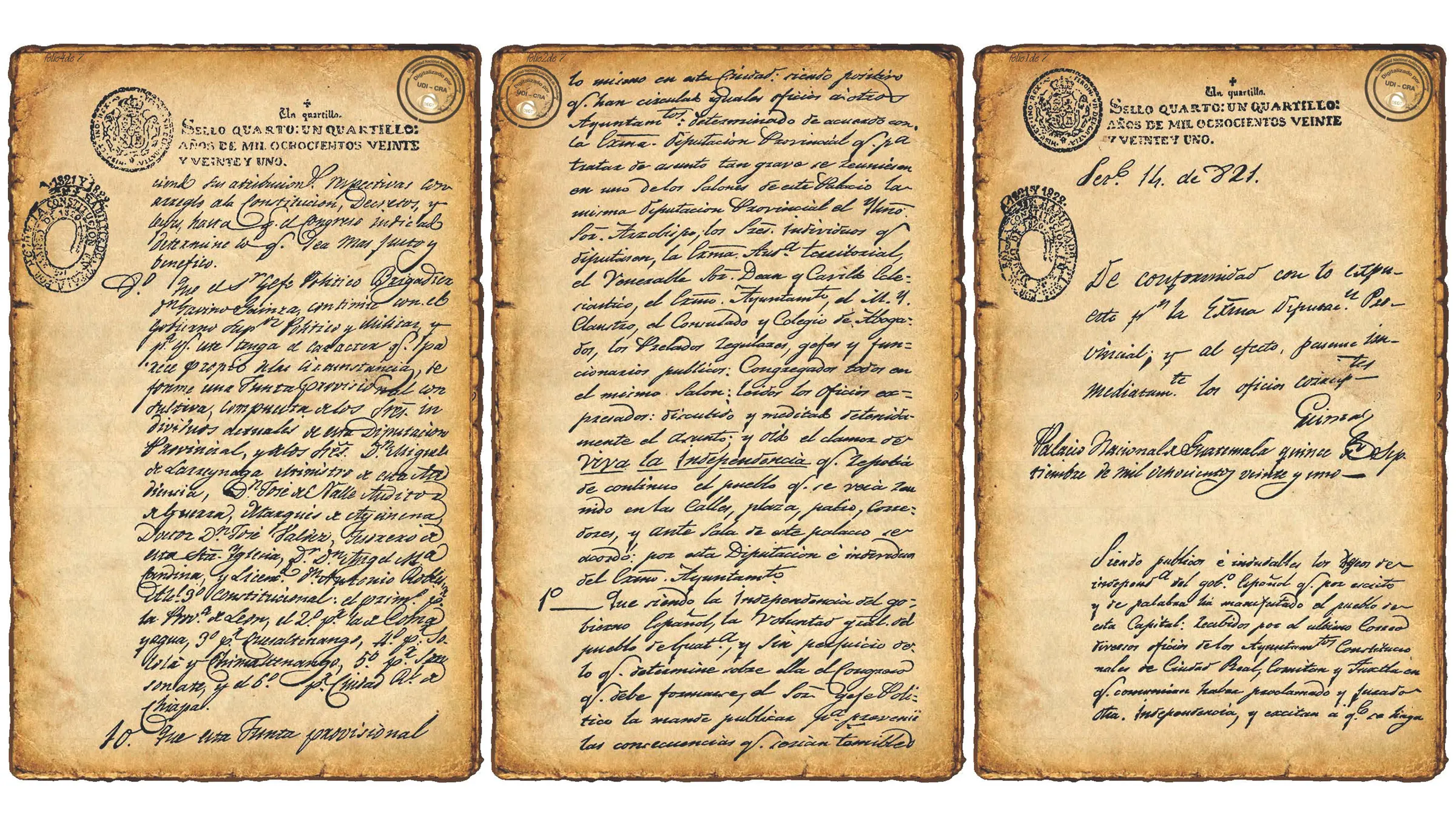

The Documents of Independence are the records containing the Act of Independence and manifestos sent from the National Palace of Guatemala to all the municipal councils of the provinces of Honduras.

After the signing of the Act of Independence in the present-day city of Guatemala, news of our independence was not known until September 28, 14 days later, with the arrival of the Documents of Independence in the cities of Comayagua and Tegucigalpa. Although the city of Gracias was the first to receive the documents on September 22.

Early in the morning of September 28, 1821, urgent messengers arrived on horseback in the towns of Comayagua and Tegucigalpa. They were expected, news from Chiapas had prepared the atmosphere. The sealed documents they brought were opened in the respective municipal councils.

They reported on the decisions made fourteen days earlier, on September 15, in a solemn session held at the Palace of the Captains General in Guatemala, and informed that Guatemala had declared in favor of independence. The characterization that Tegucigalpa celebrated the documents with joy due to its liberal stance, while Comayagua received them with reluctance as a conservative stronghold, is simplistic.

It so happened that the City Council of Tegucigalpa was controlled by Dionisio de Herrera and the supporters of independence. In March of that year, Mayor Narciso Mallol had died and his replacement had not yet been appointed. Mallol, who knew Herrera’s way of thinking, had incorporated him into the municipal administration to keep a closer watch on him. When September came, Herrera had the freedom to let the bells of freedom ring in joy.

- See the content of the Act of Independence of Honduras

- History of the Declaration of Independence of Honduras

In the always slippery realm of conjecture, were there any other forms of communication between Guatemala and Tegucigalpa besides the documents? Tegucigalpa declared in favor of fully adhering to everything agreed upon in Guatemala, as outlined in the documents. The Act of September 15 had not only been drafted but largely inspired by José Cecilio del Valle.

The Herrera family: Dionisio, Justo, and Próspero, cousins of Valle, maintained continuous correspondence with him. The two newspaper editors had played their winning card on the fifteenth. For Pedro Molina, the most important thing was to extract a declaration of emancipation from the Spanish authorities and prominent criollos. To force the hesitant ones. Since it became known that Chiapas had joined Mexican independence, agitation had been growing in Guatemala. Barrundia, Molina, and his wife Dolores Bedoya prepared the population for the session scheduled for the 15th.

The people organized by these politicians filled the streets, the square, the corridors, and the anteroom of the session hall. Article number one of the Act reflects the discomfort and undisguised fear of the summoned authorities, the illustrious colonial figures, dignitaries of the Church, members of the University Council, the Bar Association, the Consulate of Commerce, the City Council, and the Religious Orders when they determined to proclaim independence and prevent the people from declaring it themselves.

They sensed the revolution, the possibility of the people removing them from power and declaring independence. They decided to anticipate what they considered a fearsome consequence. The proclamation was followed by the burst of fireworks and displays of popular rejoicing. Molina had achieved his purpose. It was now Valle’s turn. The discussion continued and was guided by Valle. Later, he was entrusted with drafting the Act of the established agreements. Valle, the one from Choluteca, thought in provincial as well as global terms.

What was decided was the will of the people of Guatemala. But what about the rest of the cities and their inhabitants, what did they think? Hand in hand with Valle, the Act designed an electoral consultation process that would allow all other provinces to elect their representatives, who would then meet in a grand Central American congress in Guatemala on March 1, 1822. According to the Act, this March Congress would have two tasks: to ratify or reject the declaration of independence, and if approved, to determine the form of government and the fundamental law to govern the new country. The inhabitants of Tegucigalpa, encouraged by Dionisio de Herrera from the balcony of the City Hall, swore, if necessary, to defend what was decided in Guatemala. In Comayagua, the situation was different. The session was led by the Governor Intendant himself, the peninsular José Tinoco. The discussion lasted for many hours.

Finally, Comayagua also declared in favor of independence but rejected the course of action outlined in the Act and proposed from Guatemala. Given the subsequent events and the attitude of the Captain General of Guatemala, Gabino Gaínza, and other criollos from the capital, in the realm of conjecture, was there any other form of communication accompanying the documents of the Act between the authorities of the Captaincy General and those of Comayagua? With its decision, Comayagua spared itself the holding of elections and the establishment of a congress that would convene the following year to decide the form of government. Comayagua looked towards Chiapas, towards the «Three Guarantees» formula that had made Mexican independence possible. In other words, yes to independence, on the condition that a monarchical regime be established with its seat in Mexico and that all the privileges and prerogatives enjoyed by the Holy Catholic Church remained untouched and sacred.

The document took a while to reach the most important communities in Honduras:

- Gracias – September 22nd

- Comayagua and Tegucigalpa – September 28th

- Santa Rosa and Omoa – October 2nd

- Trujillo – October 6th

- Juticalpa – October 14th

- Danlí – October 20th

- Santa Bárbara – October 23rd

The city councils of these cities swore independence, if not on the same day, then the day after the documents were received. Upon learning that Guatemala had proclaimed its separation from Spain on September 15, 1821, the Provincial Delegation of Comayagua proclaimed the independence of Honduras from the Spanish Monarchy on September 28, 1821.

Dionisio de Herrera is the author of the Act of Independence of Honduras, drafted on September 28, 1821, shortly after the arrival of the documents from Guatemala. The two most important cities in Honduras were Tegucigalpa and Comayagua. In the then Villa de San Miguel de Tegucigalpa in 1821, the last Spanish mayor, Don Narciso Mallol, passed away in April, which allowed the criollo Don Tomás Midence, an exemplary citizen who had been educated under the teachings of the presbyter Don Juan Francisco Márquez, a distinguished son of Tegucigalpa who, in addition to preaching the gospel, instilled ideas of freedom to achieve independence.

Tegucigalpa was not the seat of colonial political power dependent on Guatemala, as the provincial capital was in Comayagua, but this did not exclude the fact that the Villa maintained prominence because it had distinguished patriots advocating for political emancipation. Don Dionisio de Herrera, a talented lawyer from Choluteca, after obtaining his degree from the University of Guatemala, settled in Tegucigalpa and was appointed secretary of the city council, surprising him in that year of 1821 after the death of Don Narciso Mallol as the influential official alongside Mayor Don Tomás Midence.

Herrera was an independentist and formed intellectual circles where ideas leading to the freedom of the peoples ruled by the Spanish Crown were debated. These groups included distinguished men such as Don Miguel Bustamante, Matías Zuniga, Simón Gutiérrez, Pablo Borjas, Andrés Lozano, Diego Vijil, and among them a young man who served as Herrera’s assistant and was beginning to emerge as a leader of freedom, Francisco Morazán Quezada.

Those patriots from Tegucigalpa were considered by the authorities in Comayagua as conspirators, arousing suspicion for promoting ideas contrary to the colonial regime that was already in agony due to the Independence proclaimed by Chiapas and in previous years when in Mexico in 1810, Father Hidalgo launched the cry of Independence in the town of Dolores, and the towns of Gran Colombia in 1819 broke away from Spain.

On September 15, 1821, the independence of the Central American peoples was proclaimed, and the news of the event reached Honduras thirteen days later when the Consultative Board sent a faithful copy of the document containing the declaration signed by the patriots through special land mail. Comayagua received the documents early in the morning on September 28, and the government, along with the members of the city council, learned of the decision, accepting independence but disregarding the authority of Guatemala and recognizing it as Chiapas had done to the Empire of Mexico.

The Villa of Tegucigalpa only found out in the afternoon of that day, and immediately the City Council, led by Don Tomás Midence, proceeded to summon all civil and ecclesiastical authorities and called on the people to gather in the square to be informed of the significant news. Independence was sworn, and Secretary Herrera recorded in the minutes the loyalty of the noble City Council of the Villa of Tegucigalpa to the Consultative Board of Guatemala.

From the balcony of the City Council, the patriots announced the good news, the bells of the City Council and all the churches, including the parish of San Miguel, San Francisco, Los Dolores, El Calvario, and the Inmaculada Concepción, rang joyfully, filling the atmosphere of the town. Fireworks were lit, and at night, Tegucigalpa was illuminated by torches and the traditional bonfires in front of houses.

Among the most prominent Honduran figures in Central American history is José Cecilio del Valle, the drafter of the Declaration of Independence signed in Guatemala on September 15, 1821, and the Chancellor of Mexico in 1823. Honduras separated from the Central American Federation in November 1838 and became a sovereign and independent state. Despite all these events, Spain only recognized Honduran independence on March 15, 1863, which was celebrated on September 28 each year until the date was changed to September 15 in 1877.